Some scenes grab your attention instantly. But while some frames give you a clear story or a message as they draw your attention, some others appeal to you with a vague, yet strong sense of symbology. You don’t quite know what that particular scene means and why it appeals to you. But you know that there is something that the frame is trying to tell you. And at the end of the day when you sit down and reflect back on the day’s encounters with a calm mind, it becomes clear to you.

This photograph is an example of one such frame.

After 10 days of busy and packed Pushkar cattle fair in Rajasthan the villagers had started leaving Pushkar to go back to their home villages. As I walked through the fair ground, I saw villagers walking in the opposite direction with their camels. I felt vague sense of sadness and nostalgia seeing the beautiful mela come to an end.

In all that commotion, this scene caught my attention. Pairs of abandoned shoes lying in muddy puddle.

Now when I think about it, these abandoned shoes were a great symbology for what was happening around me. With time another Mela was coming to an end, and after living on these open grounds the villagers and travellers were moving on with their lives. But not without leaving a part of themselves behind in memories and things.

May be this is what these abandoned shoes were trying to tell me. That to keep moving with passing time is part of life. But experiences and places leave a lasting mark on the people, and people, knowingly or unknowingly, leave a part of themselves in places they go to in different ways.

rajasthan

Tale Of The Untouchable Bawariyas Of Rajasthan

During our journey through rural Rajasthan, we came across the Van Bawariyas tribe, a hunting gathering tribe of Rajasthan.

The Wildlife Protection Act (WPA) of 1972 which apart from declaring hunting these animals as illegal, surprisingly, it also criminalized the status of Bawariyas.

Hunting was a livelihood skill for these people, but since hunting was criminalised they were forced to look for other ways to live and survive.

“Do you still practice hunting?,” we asked Radha. With an exasperated sigh, she said, “No, not anymore. Don’t judge us for what we did. This is all we had and this is what we were expected to do for centuries. We have started doing menial jobs now that get us enough money to survive from day to day.” Like her, the rest of her family has lost all hope and no longer do they long for a better life. Today, Radha is not sure if she will live to see a day when all her troubles might vanish; where her children will no more be accused of crimes committed by their forefathers.

Sometimes, they volunteer to take goats out grazing into the fields or go to Nawa near Sambhar Jheel and assist in salt production. But most of the time, they fill up tractors with sand and sell the entire lot for a meager sum of Rs 500. “That’s how we earn our living now. We are not skilled at anything else. How are we supposed to survive? How can the government declare something illegal without considering what our identity has been so far? How can they order us to stop doing the only thing we know and not provide an alternate solution?” asked a teary-eyed Bangaram.

A few months earlier, a government official from the Flying Squad or perhaps an imposter, no one can really be sure, visited the clan and threatened to complain against them. Simply, because they are Bawariyas and could probably slide back to their old devious ways of living — one that was hugely advocated by royalty alike back in the day.

Despite stringent laws, the villagers continued to consume teetar from time to time. Eating such delicacies was a part of their lifestyle. And, the Bawariyas were expected to deliver them no questions asked. “That would earn us Rs 150 to Rs 200. When the person from the Flying Squad accused us of treachery, we begged him to show mercy. He told us that we would be arrested and sentenced to a prison term of 20 years. We ended up giving him all our savings. After that, we never heard from anyone. All that we had earned or inherited was gone,” said Bangaram.

Gradually, the clan was forced live like vagabonds amidst filth and dust. Sab loot ke le gaye who flying waale. Sab peesa le gaya… Radha’s voice echoed from the corner.

There are no more animals left to hunt in the area. Yet, Bawariyas are constantly accused of committing a crime that is a punishable offence in the country. As soon as we were done talking to the family, we walked towards the next set of tents in the vicinity. Here, we met Bajrang who narrated to us devastating stories that left us distressed and shaken.

“Kya fasal karenge hum idhar? Hum toh bhooke mar rahe hoon. Yahan toh sirf mitti hai. Yahan kuch nahin ugta. (What do we grow here? We are all dying here. There’s nothing but sand all around. Nothing grows on these terrains),” said Bajrang.

Neither has the government provided them with basic facilities that the society deems necessary for survival nor have they taken any measures to ensure that life for them becomes bearable.

“They have enslaved us. We are prisoners here. In all, we are about 150 or 200 people. I was born here and I will die here. We don’t have electricity or water. The least they can do is provide us water on time. Don’t I constitute the society?” asked Bajrang.

After repeated complaints, a single tap was installed for the entire clan in the area. Water is provided for an hour everyday and all of them are expected to survive with what has been given to them. It is a game of probability. Everyday they wonder whose turn it is to go thirsty today. No one should be treated like this! It is nothing but a sign of barbarism reigning supreme in a society where one is still targeted for belonging to the lower caste.

“We were told that we are animals and don’t deserve any of these facilities. I am a human being and I most certainly deserve dignity and respect from fellow individuals if not materialistic possessions. We even told them that you can take some money from us and get more taps fixed. If we had water, why wouldn’t we take a shower? Why wouldn’t we be more presentable?,” asked the young lad.

A few children were seen playing around a broken pillar that was installed by the Sarpanch and the Police Department a few weeks ago to facilitate a continuous supply of electricity within the area. Now, the pillar is in a shambles. Before elections, there were several politicians who visited the group and made ‘bold’ empty promises. They were told that all their problems would be addressed and that they would be given everything that they had been deprived of so far. They would be welcomed back with open arms to human civilization and no longer would they have to live a life of recluse and misery. After the requisite 200 votes were secured from the community, they were forgotten and left to drown in their own sorrows.

“Pehle bola phool main vote dena aur hum sab theek kardenge. Kuch nahin hua. (Vote for the flower. We will solve everything. Nothing happened). At least, if some scheme comes out where we get Rs 500 per month from the government as pension, we will be able to survive. How are the elderly folks supposed to go out and look for work?” inquired Bajarang. For these people, every single day in the past few decades has been a constant reminder of the fact that we live in a world where trust is betrayed and souls are slaughtered without any remorse or regret.

Even if they go to the Sarpanch to complain or ask people from the Panchayat to address their issues, they are looked down upon. Moreover, thanks to a few backward practices still prevalent in major parts of rural Rajasthan, the family is unable to educate their children and send them to school. In a modern context, these practices are usually categorized as socioreligious and involve the outrageous ritual of ostracizing a group by separating them from everyone else or in other words untouchability. Those who live in an era where equality is a mythical concept perhaps best understand the perilous nature of this particular practice.

As a result, most of the Bawariyas find it impossible to educate their children even if it is their fundamental right to send them to the same school as the rest of the villagers. “A few of our kids manage to sneak into schools and attend classes every so often. On numerous occasions, kids and teachers who belong to the Jaat or Baniya community gang up against our children and tell them, “Tum toh achuth ho. Hum tumare saath nahin padh sakte. (You guys are untouchables. We cannot study with you),” explained Bajrang who further added that they keep trying to bring these issues to the notice of the authorities but what can they do if they have absolutely no support from the government — the very establishment that is supposed to cater to our needs. Hypothetically, if everyone decided to step out of their boundaries and travel to distant places, they wouldn’t have to conform to societal norms prevalent in their own territory. In unknown lands, even foes turn to seek connection witheach other. And, the Bawariyas have borne witness to all such behavioral tendencies.

The worst affected in this mindless battle are the children. The atrocious behavior towards them breeds hatred and spite within their hearts. And, before they can even comprehend what hardships of life or struggle for survival means, they are thrown into the battlefield. Their childhood is stolen mercilessly from them. Innocent souls that belong to the realms of fantasy and adventure are now spewing venom and challenging each other’s integrity.

“I have stopped going to the police now. No one takes me seriously. They look at me with disgust and tell me You can’t even keep yourself clean! You have no water to drink! Are you an animal or a human being? Sometimes I wonder why am I still alive? What’s the point of living like this? I hope I find peace when I die. That’s all I have left to look forward to, ” said Bajrang with a heavy heart.

Until next time, my dear friend…

He stares down at his little friends day in and day out. Their passion and vigour amuses him. They treat him like their own and not once did they ask him for anything in return. They admire his beauty and love him dearly. Sometimes, their dangling feet make beautiful sounds against his skin. They belong to him and he belongs to them…the giant ferriswheel.

Behind him Salman and his gang of tiny minions create a ruckus on his buddy — the mini roller coaster ride. It has been a month since the Pushkar Mela was held. The area that was once occupied by tens of thousands of animals and villagers now lies empty; abandoned by those who called it home for a while. The sea of plastic and garbage visible on the open landscape is vaguely reminiscent of the camel fair that took place in these soils.

A stroll down the narrow roads will reveal a picture devoid of any activity or celebration. Though the mela is officially over, the giant rides are still seen hovering — tall and lifeless — over the market. After a few moments, there’s a resounding echo of laughter in the air. A group of ten or twelve kids who had occupied the roller coaster ride earlier are seen engrossed in a game of catch-and-release.

For these children, most of their childhood is spent on these giant life-sized toys. Today, the amusement rides have become their ‘imaginary’ best pals, a place to enjoy an afternoon siesta and perhaps their most exotic playground. But, most importantly, it is a place where they can leave all their worries behind and enjoy the warmth of joy; a place they can call home.

Most of their days begin and end with spending time on these massive toys which are now being pulled apart a little by little everyday only to be re-assembled in another mela. It is an emotional journey for these tiny tots as they observe their gigantic friends – Ferris, Columbus and Rollercoaster — being torn to shreds; as they bear witness to a reality where dreams and fantasies cease to exist.

They wait in anticipation for their friends to be brought to life. However, their fears and anxiety betray their emotions. And, as each of them lingers a little while longer around their lifeless companions, wondering how long do they have to wait this time to see their best friends, they secretly hope that they don’t have to move on.

Until next time, my dear friend…

***********

This is a story through the eyes of the children belonging to families that put up amusement rides for several melas throughout the country. While the children spend most of their time in the villages, their parents travel for eight months in a year. Whenever time permits, kids visit their parents and have a ball on the amusement rides.

The Day We Met Krishna

Walking around the fields in Ranseesar Jodha village we came across a family that had built their home in the fields a little away from the village. There I saw a mother working in the fields while her two year old daughter sat around playing in the sand.

We sat down and spent some time talking to the family and hearing their stories.

As we spoke I said that Krishna, the baby girl is very cute to which the mother jokingly said why don’t you guys take her with you. Even though female child infanticide has reduced over the years, the joy of having a boy is much more as opposed to that of having a female child. It is not that parents don’t get attached to their daughters, they very much do. Girls are pampered more than boys too because one day they will get married and go away. But poverty makes these poor families favour having a boy more than a girl because boys will earn a living for the parents when they grow old. The father in between the conversation said – “one day the girl will get married and go away and the money will go as well. Even if she earns she will earn for her family not for us.” The love the mother had for Krishna was affectionately obvious.

The present and future of daughters in Rajasthan, a daughter and a mother- one is shy of the reality and the other has been hardened by the reality of life.

The right way to discourage female infanticide is not by making it illegal, but by understanding the root cause behind the tendency which is poverty.

Nagada Making

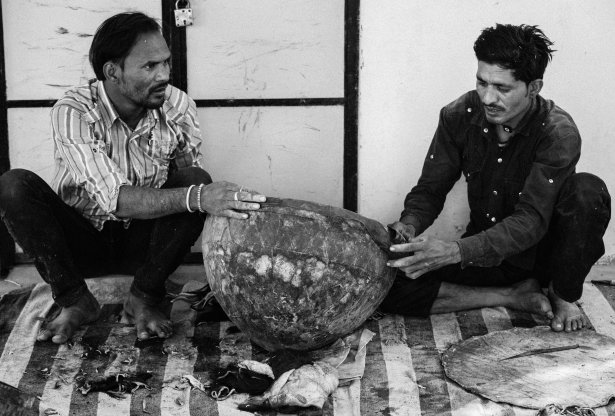

One afternoon during my stay in Ransisar Jodha village, Sitaram came over to the house I was staying in and told me that there were two people who had come to the local temple to make Nagadas (Traditional Rajasthani drums) . I immediately took my camera and followed Sitaram to the temple complex near by.

At the temple I met Vinod and his brother who were the leather working class/caste of Rajasthan and they had followed in their father’s footsteps and taken up Nagada making as their profession. The main body is usually made up of Iron and buffalo skin is used as the top membrane and for tying the membrane to the body.

This is a B&W photo series, trying to cover the nuances of the process.

Lost Divinity…

There was something intriguingly interesting about seeing decapitated idols lying deserted by the road side in middle of no where. May be because of the contrasting reverence, purity, respect and divinity they are otherwise dealt with in the society. So I decided to do a small photo story on one such place I came across on one of my daily explorations.

Seeing idols in this condition, for me, is representative of the inevitable transition in the symbolic values of all objects and things.

Bangadi Kids

During one of my many travels into the villages of Rajasthan, I found myself passing by Kharekhadi village. It was full of life and having gone through the length of the village, on my bike, I decided to turn back and walk around to find a group of nomadic sheep herders that I had caught a glimpse of passing by.

I tried to ask around and trace the herders but I couldn’t. And, as I was walking around the dusty narrow lanes hoping to find them, I came across a few kids playing with a make-shift improvised push cart sort of a toy that caught my fascination. The kids referred to the toy as ‘Bangadi’. For me, it was sophistication hidden in simplicity. They had made the Bangadi using a broken old flip flop for the rear wheels, base of a geometry box, a flip flop for the body and a wire for the steering and front wheels.

Where some might find poverty and scarcity, some others might see innvovative/improvising/recycling skills.

What these pictures mean to different people is subjective and may even be debatable. But what is unequivocally clear is the happiness these kids live and experience everyday by making best use of what little they have.

When the skies were dotted with kites…

Blanketing the earth in an infinite band of celestial wonders, the heavens celebrated the magic and wonder of flight as earthlings adjusted their kite strings to the echoes of wind and earth. Whilst the streets of Pushkar were deserted and seemed to have come to a standstill; the young and old alike gathered on rooftops to celebrate the eternal transition of the sun from one zodiac sign into another. Makara Sankranti or the harvest festival is an ancient ritual to immortalise the celebration of collective energy, of the spirit of our connection with nature and the dawn of spring. And, it is no wonder that at this time of the year, new relationships are formed, new friendships made and everyone bonds with one another sans any prejudices or preconceived notions.

As the winter morning welcomed the warm embrace of sunshine, kites were seen drifting across the horizon chasing the pre-dawn wind. The ritual of waking up early in the morning waiting for the dawn to turn into a congregation of opal and pink, just to pick the perfect spot before the skies turn into a riot of colours, is followed very sincerely amongst the children here. As the day gets brighter, the cool breeze lifts the kites aloft into the horizon and the rooftops are dotted with hordes of families challenging and coaxing each other to battle it out with kites.

With each and every household blaring music ranging from psychedelic trance to Bollywood and bhajans, the kite flying ‘ritual’ in any town gives rise to a phenomenon where social gatherings are no longer marred by pretentious greetings. A lot of terraces had music systems stacked up in a pile and a few teenagers engaged in a comedic battle of wits with their rivals on loudspeakers. Eager faces and enthusiastic souls invited curious onlookers onto their roofs by yelling out “Aa jao Aa jao lada lo. (Come. Let us have a match).” We soon decided to head towards a Dharmshala where all the action could be easily witnessed.

The sight of smiling faces perched on rooftops; eyes gleaming with mischief and childlike enthusiasm filled the air with warmth and happiness. Children were seen climbing walls and pipes to steal a kati patang or scan the best roof for optimum flying conditions. There were instructions being given out with military precision by five and six-year-olds. For them, the stage had been set and the battle was in motion.

While mothers draped in bright Bandhni saris were seen helping out their tiny toddlers balance the charkhi and manjha; a few grandfathers, smoking beedhis with a lot of panache, tried their best to bring down their neighbours’ kites. Also seen amidst a crowded settlement was a newly wed Rajput couple, dressed in their traditional attire, who exchanged glances at each other as they flew their kites. By evening, multicoloured kites and numerous birds crossed paths and one couldn’t make out the difference between our little avian friends and their lifeless flight companions soaring in the skies.

There was poetry and romance in the air and every person was inebriated in the spirit of celebration. For a change, no one was judged based on his/her caste, community, creed or even social status. There was no rich and no poor here for all gathered on their roofs as one. For those few moments, all worries and hardships were forgotten and every person indulged in the age-old past time of bonding over a ritual that epitomised connections based on unity and love. And as the warmth of sunshine drifted away from the Southern hemisphere to the Northern, everyone welcomed the rays of new hope, as customary every year, with great reverence and joy.

Kids At Pushkar Mela

Many of the nomadic village families who come to Pushkar Mela to trade cattle, doll up their kids, and send them out to make some money from the tourists and photographers. These kids try their best to get some money out of the travellers, but walking around the dusty and sunny mela, the kids feel the burden of making a living at their young age.

But kids are kids and they don’t yet understand all the nuances of earning a living and find some time out to have some fun and be themselves – careless and free.

This is a small photo series on one such group of kids through which I am trying to show how a young boy was sent out with a turban and a ravanhatta (bowed fiddle/a musical instrument local to the state of Rajsthan) to attract the attention of photographers and make some money.

He and friends knew very little about making a living or playing the instrument and had very little interest in making any money. But the poor economical condition of their families leaves these kids with no other options. Struggle for life is not a new thing for these kids.